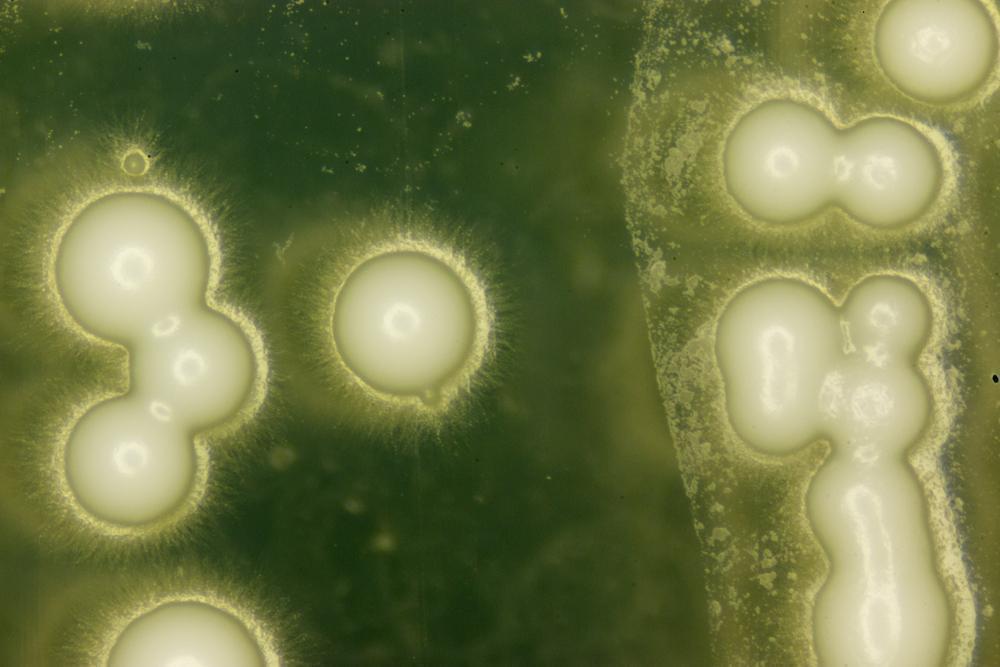

The microbiome was first defined in 1958. It was identified as the collective genome of the microorganisms that share body space. These microorganisms include bacteria, archaea, virus, and fungi.

It is believed that 90% of human cells are not of human origin; hence the saying we are only 10% human. Microorganisms of the microbiome therefore provide an important genetic variation. Bacterial genes provide diversity and functions that human cells do not have. This similarly applies to our pets.

The microbiome is an important modifier of disease and an essential component of immunity. Dysbiosis of the many microbiomes have been associated with a range of disorders and each day we are learning more about more about the community inside and on top of us, and our pets. Whilst our research is still getting a handle on things, and there are many things we still don’t know much about, we know that certain things can skew the microbiome to result in dysbiosis, and there are somethings than can help it sort itself out.

Let’s take a look.

The intestinal microbiota is the collection of all microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract. The microbiome is the collective genome of these microorganisms.

Bacteria make up most microbial cells, showing an increase in abundance from the stomach to the colon.

The predominant phyla in the GIT of healthy dogs are:

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes,

Actinobacteria, and

Fusobacteria

But each individual animal will have their own personal profile.

A note on testing… it would stand to reason, that if we know the bugs that contribute to healthy microbiomes and those that can start to run amok, if we could test for them, then we could tailor a microbiome for health? This is a great concept and one that is gaining traction in the human world, but we still haven’t established a perfect microbiome or microbiota. As it stands, we need to learn more – and acknowledge that our microbiomes are unique – what may be perfect for your dog, may not be perfect for mine.

We know that certain bacterial groups have consequences – both beneficial and potentially deleterious.

For example, certain dietary carbohydrates can be fermented by the microbes in the gut – in this process, they produce short-chain-fatty-acids. These are known as butyrate, acetate and propionate. On the plus side, these compounds are anti-inflammatory, they maintain intestinal barrier function, regulate motility (the movement of the digestive system) and also provide energy for epithelial cells. On the downside, they can activate virulence factors of enteropathogens.

In addition, bile acids also seem to be a major regulator of the gut microbiota. Liver health is therefore implicated in microbiome composition as reduced bile levels are associated with bacterial overgrowth and inflammation. Secondary bile acids have been seen to inhibit the growth of clostridum difficile, Escherichia coli and more. They are also seen to modulate glucose/insulin secretion from the pancreas. Bacteria in the gut produce these secondary bile acids and so if they aren’t present, their antimicrobial function is missed!

Dogs with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency have significantly reduced bacterial diversity, with lactic acid bacteria Bifidobacteriaceae, Enterococcaceae, and Lactobacillaceae increased, likely because of overgrowth associated with maldigestion. As we know, the pancreas produces enzymes that help digestion, so if this isn’t occurring upstream in the digestive process, it can cause problems further down. If you would like to know more about the digestive process that occurs in the dog, check out our blog:

The Digestive System of the Dog

Many studies have highlighted the alterations in bacterial diversity in a range of conditions in the dog. So, what can result in these alterations in bacterial diversity?

Generally, the major types of dysbiosis fall under 4 categories.

- Abnormal substrates in digestive tract

- Loss of beneficial commensal bacteria

- Increase in total bacterial load

- Increased pathogenic bacteria

Abnormal Substrates in Digestive Tract

The most common here are undigested nutrients – if there is low stomach acid, digestion is impaired resulting in undigested nutrients moving through the digestive tract. If the pancreas isn’t fully functioning and releasing those helpful digestive enzymes, the same applies. The other abnormal substrate includes medications – which

may result in changes in the microbiome.

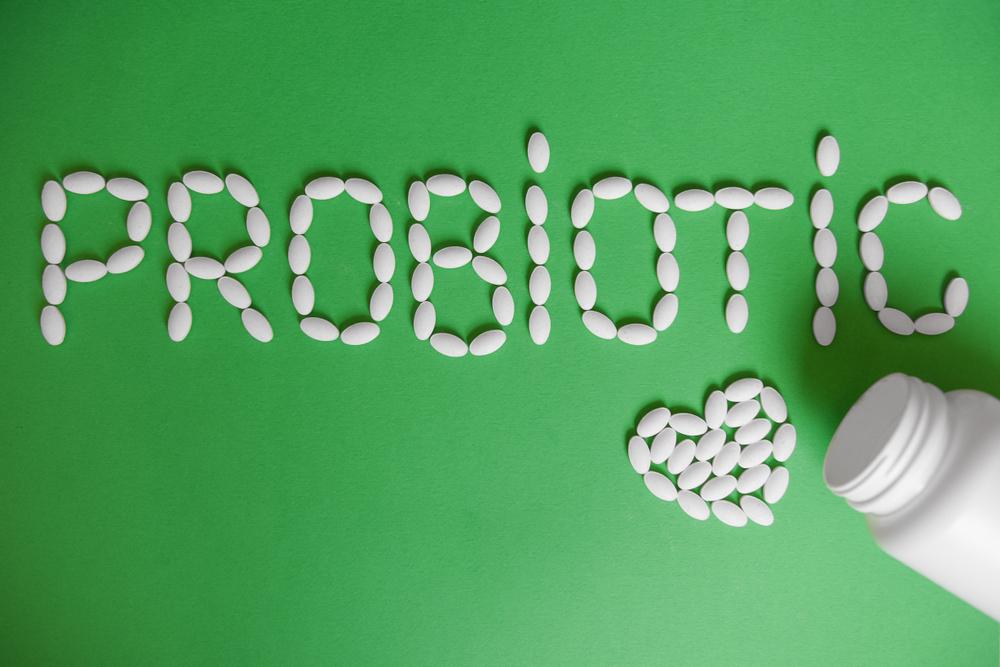

Loss of Beneficial Commensal Bacteria

The most common cause of loss of commensal bacteria is the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics (BSA) – BSAs aren’t fussy – they’ll do their job perfectly, taking all bugs with them – this includes those beneficial commensal bacteria that keep the bad guys in check, and which help produce metabolites for optimal functioning.

Of interest here is the mechanism by which antibiotics can affect the chemical transformation of pesticides. Antibiotics, through their bug killing capacity, have been seen to suppress enzymes required in hepatic metabolism and also increase intestinal absorption leading to improved bioavailability of pesticides and therefore skyrocketing their risk factor.

Findings Here

Increase in Total Bacterial Load

This is more relevant in cases of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. When we reference the microbiome, we are considering the microbial community found in the whole of the digestive tract. Generally, the further down we go, the more bugs we find. For this reason, we would expect the majority of the bugs to be found in the colon. SIBO is when there are higher numbers found in the small intestine.

Low stomach acid can contribute to the development of SIBO – and the administration of proton pump inhibitors and antihistamines can both suppress gastric acid secretion.

Poor motility can also contribute to the development of SIBO, and stress can be a huge factor that contributes to motility issues. In short, if the digestive system isn’t moving, food particles sit where they shouldn’t. Increased bacterial load is what occurs in yeast issues for example. Candida is harmless when kept in check, but for a number of reasons it can overgrow. If you would like to learn more about yeast, check out our blog:

Is your Dog a Yeasty Beast?

Increased Pathogenic Bacteria

No-one will knowingly ingest pathogenic bacteria – we can’t speak for your poop eating dogs – but there are other mechanisms by which pathogenic bacteria can be increased in the gut and stress is a major contributor.

It is well known that both chronic and acute stressors can shift the gut bacteria in multiple regions and habitats. In addition, those pesky catecholamines (stress hormones) can increase certain bacterial levels 10,000-fold – they can also increase their infectiousness in just 14 hours! These pathogenic bacteria may crowd out the beneficial species. In the same strand, stress also contributes to gut permeability – so not only are there more infectious bugs, but they can also translocate – causing inflammation throughout the body!

Findings Here

Diet choices too affect the composition of the microbiota.

The Western diet in humans, high in saturated fat, processed foods, and refined sugar, starkly contrasts with fibre-rich, plant-based diets of indigenous cultures. The Western diet fosters a distinct gut microbiota signature with low gut microbiota diversity and greater gut leakiness.

Studies have demonstrated significant changes in dog microbiota compared to grey wolf microbiota, largely due to dietary differences; and their evolutionary need to adapt to changes in food consumption.

Findings Here

So, if we were to sum up what can contribute to dysbiosis in the gut:

- Overuse of antibiotics

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Antihistamines

- Poor liver function

- Poor motility

- Digestive disorders

- Poor pancreatic function

- Inflammation in the gut

- Stress

- Environmental toxins

- Dietary choices

But this list is not exhaustive – gut health is almost like the butterfly effect; seemingly small things can greatly impact a complex system.

So, what we can do to promote an optimal microbiota for our dogs? That is a blog of its own. In the short term, it’s the opposite of what can result in dysbiosis – but come back soon and we’ll look at it in more detail.

If you would like any support for your pet’s digestive system or health, then please check out our services.

Thanks for reading,

Team MPN x