Why Is My Dog A Fussy Eater?

- January 18, 2021

- 10 min read

Any quick search on the internet will populate a range of breeds that are seemingly notorious for being fussy eaters. If you have a basenji, husky or yorkie, it looks like you’re signed up for a lifetime of stressful meals. Except here at My Pet Nutritionist, we don’t believe everything we read on the internet. Whilst all those breeds could indeed be fussy eaters, so can many more. And they are. It is perhaps one of the more common questions we are asked, “how can I get my dog to eat?”

Being a fussy eater can be technically defined as an eating disorder, and there are a number of causes. From behavioural to biochemical, let’s take a look at the complex world of the fussy eater.

The Function of Eating

Food components are the main sources of energy for the canine body. Not only that, but it provides the compounds needed for each cell to do its job.

As the body carries out its tasks, it uses fuel and compounds, as reserves run low, signals bounce around the body to kickstart feeding behaviour. This is hunger, a physical need to eat.

Appetite is quite simply the desire to eat. Hunger and appetite can be at odds. You may want to eat, but not need to, and you may need to eat, but not want to (in times of stress for example).

Appetite and hunger are largely controlled by the brain and a range of hormones.

The Brain

In the brain sits the hypothalamus. Through its connection to the pituitary gland, it modulates the endocrine system. It is involved in a range of daily activities including temperature regulation and energy maintenance. We know it plays a role in eating behaviour as several lesions to small areas of it can result in overeating and under eating. The lateral hypothalamus is defined as the feeding centre and the ventromedial hypothalamus is defined as the satiety centre. This is largely an oversimplification, but it certainly demonstrates the role.

The hypothalamus receives information from the digestive system like stomach extension, chemical nature of ingested food and the metabolic activity of the liver and uses it to maintain energy balance.

It also receives information from the emotion/reward system. Food is a rewarding object that induces pleasant emotions.

Findings here

The amygdala is largely responsible for this. Studies have demonstrated that when the reward value of food decreases, so too does eating motivation. Sadly, these studies often include the injection of lithium after eating, of which causes discomfort. But it does raise an interesting point in terms of the fussy eater in your life. We’ll revisit this later.

Food reward is elicited by several events that occur before it even passes through the oesophagus, namingly the appearance and shape of the food, the taste and smell and then the pleasure of swallowing the food. We know this because in tube-feeding studies, reward sensations are reduced. In short, when subjects were no longer allowed to taste or chew it, they did not want to eat it. That said, in sham studies, when animals are denied nutrition because everything swallowed leaks out of a tube connected to the oesophagus, they eat and swallow more than usual, but they are still unsatiated. This tells us just how complex eating behaviour actually is. And provides food for thought for the gluttonous dog (on the other side of the scale).

Hormones

Hormones are probably the most talked about in terms of eating behaviour. You’ve all likely come across leptin and ghrelin.

Leptin is produced in adipose cells, or fat cells. So, the more fat cells there are,the more leptin. In short, the more fat available in reserves, the less you need to eat. If you have no fat cells, you need to conserve your energy until you next find food. Leptin crosses the blood-brain barrier, and there are high numbers of leptin receptors found in the hypothalamus, brain stem and other regions of the brain. Rising leptin in a fed state inhibits food intake by suppressing a range of peptides involved in eating behaviour.

Ghrelin is predominantly secreted in the stomach and it too modulates cells found in the hypothalamus by increasing excitatory inputs and decreasing inhibitory inputs. Here we are talking about neurotransmitters. These chemical messengers modulate much of our and our pet’s behaviour and they either make something do something or stop something from doing something.

Whilst dopamine can be both inhibitory and excitatory, ghrelin is seen to have a large influence on the release of dopamine via increases in cell excitability. As dopamine is involved in reward and motivation, ghrelin is thought to target the motivational functions geared to gaining food and to select those which are more rewarding (high calorie).

Findings here

In eating disorders, dopamine is one of the neurotransmitters that gets a lot of attention.

In times of reduced food intake (fussy eating), dopamine neurons are activated, in the short-term rewarding the lack of food. It is considered that it is a physiological response in an attempt to increase motivation to forage for food.

Findings here

However, there are also other mechanisms in which the dopaminergic system comes into play for the fussy eater. A central feature of the dopamine neuron response is that it is triggered by unexpectancy.

After receiving an unexpected reward like food (or how many likes our recent post has got on social media) a dopamine surge is elicited.

When this becomes a regular occurrence, the dopamine signal is triggered by the conditioned stimulus in predicting the reward. However, the dopamine system does not respond when the reward is received. If the reward is predicted, then not received, there is a dip in dopamine activity. What this means, is that your dog may do the song and dance ready for their bowl of food, but then walk a way as soon as it is placed in front of them. The reward they predicted (tasty food), isn’t what was received.

The other neurotransmitter that gets a little attention in terms of eating behaviour is serotonin.

5-HT has a well confirmed role in the regulation of eating behaviour. Manipulations to increase it have led to reduced eating behaviour and those to reduce it precipitate binge eating behaviour.

Findings here

This suggests another multifactorial mechanism that indirectly effects eating behaviour.

Serotonin is a key player in feelings of nausea – so higher levels could be produced in response to something not sitting quite right in the digestive system.

Poor serotonin metabolism can also contribute to high levels.

Whenever something is produced in the body,it needs to be used and then broken down. Serotonin is metabolised largely by monoamine oxidase (MAO) so it stands to reason that MAO inhibitors can contribute to high levels in the body. Sadly, certain insecticides found on flea and tick collars contain MAO inhibitors.

Findings here

There are also certain dietary supplements that can increase 5-HT including ginseng, turmeric, rhodiola rosea, l-theanine and St. John’s Wort.

There is also the link between high serotonin levels, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive type behaviours, suggesting that there is also a place for stress behaviour coinciding with fussy eating patterns.

Stress

Stress is a biological response to a perceived threat. It consists of two elements; the fight or flight response and the rest and recover response. During the fight or flight response,resources are directed to where they are needed and away from the digestive system.

This we can get on board with. How many times, during stressful experiences,have you just not wanted to eat? Corticotropin-releasing hormone is released as part of the stress response, and it is conclusively linked with decreased eating patterns.

Findings here

This can apply to our dogs too. If they are faced with chronic stressors like health issues or environmental challenges including people and other pets, then their resources will largely be diverted away from their digestive system.

Yet, there is also evidence which links stress to increased eating patterns. This is largely due to the resources utilised in the stress response and the body seeking energy-dense foods. Repeated and uncontrollable stress dysregulates the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis; this in turn activates the dopaminergic system of which we mentioned earlier. This is why hyperpalatable foods are so important, if in fact you are addressing eating behaviour during and when recovering from a stressor.

So where does this all leave us when tackling a fussy eater?

They could of course simply not like the food they are being offered. In terms of reward pathways, it’s just not lighting their fire.

There could be some learned behaviour that is telling them to avoid the food on offer; if they have felt rubbish after eating it before, then they’d do well to avoid it in future. This doesn’t even have to be sinister in terms of a gastro bug, it could merely be a sensitivity. It could be due to lack of digestion from a poorly functioning liver or pancreas. Long term medication use could have resulted in limited stomach acid or there could be poor integrity in the gut that warrants some healing. There could be a range of underlying issues like GERD or SIBO, of which just make mealtimes and the following digestion, particularly uncomfortably. This can also apply to dental issues. Whether current or past. Dogs are incredibly good at hiding their pain or discomfort, it wouldn’t have boded well in terms of evolution; a sign of weakness places them as an easy target for predators. So, its up to us to observe and notice patterns in their behaviour.

We must also consider stress. For both human and pet. If they are exposed to acute or chronic stress, it could remove their desire to eat. That said, as an owner managing a fussy eater, the owner too can become stressed and anxious that the dog isn’t getting the nutrients they need to thrive. Unfortunately for us, dogs have incredible olfactory capabilities, meaning they can smell our stress! They also have this capacity to mirror our emotions. And so, when they don’t eat,we get stressed, so they get stressed and may be even less likely to eat.

Top Tips for Managing a Fussy Eater:

Thanks for reading!

MPN Team x

Being a fussy eater can be technically defined as an eating disorder, and there are a number of causes. From behavioural to biochemical, let’s take a look at the complex world of the fussy eater.

The Function of Eating

Food components are the main sources of energy for the canine body. Not only that, but it provides the compounds needed for each cell to do its job.As the body carries out its tasks, it uses fuel and compounds, as reserves run low, signals bounce around the body to kickstart feeding behaviour. This is hunger, a physical need to eat.

Appetite is quite simply the desire to eat. Hunger and appetite can be at odds. You may want to eat, but not need to, and you may need to eat, but not want to (in times of stress for example).

Appetite and hunger are largely controlled by the brain and a range of hormones.

The Brain

In the brain sits the hypothalamus. Through its connection to the pituitary gland, it modulates the endocrine system. It is involved in a range of daily activities including temperature regulation and energy maintenance. We know it plays a role in eating behaviour as several lesions to small areas of it can result in overeating and under eating. The lateral hypothalamus is defined as the feeding centre and the ventromedial hypothalamus is defined as the satiety centre. This is largely an oversimplification, but it certainly demonstrates the role.The hypothalamus receives information from the digestive system like stomach extension, chemical nature of ingested food and the metabolic activity of the liver and uses it to maintain energy balance.

It also receives information from the emotion/reward system. Food is a rewarding object that induces pleasant emotions.

Findings here

The amygdala is largely responsible for this. Studies have demonstrated that when the reward value of food decreases, so too does eating motivation. Sadly, these studies often include the injection of lithium after eating, of which causes discomfort. But it does raise an interesting point in terms of the fussy eater in your life. We’ll revisit this later.

Food reward is elicited by several events that occur before it even passes through the oesophagus, namingly the appearance and shape of the food, the taste and smell and then the pleasure of swallowing the food. We know this because in tube-feeding studies, reward sensations are reduced. In short, when subjects were no longer allowed to taste or chew it, they did not want to eat it. That said, in sham studies, when animals are denied nutrition because everything swallowed leaks out of a tube connected to the oesophagus, they eat and swallow more than usual, but they are still unsatiated. This tells us just how complex eating behaviour actually is. And provides food for thought for the gluttonous dog (on the other side of the scale).

Hormones

Hormones are probably the most talked about in terms of eating behaviour. You’ve all likely come across leptin and ghrelin.Leptin is produced in adipose cells, or fat cells. So, the more fat cells there are,the more leptin. In short, the more fat available in reserves, the less you need to eat. If you have no fat cells, you need to conserve your energy until you next find food. Leptin crosses the blood-brain barrier, and there are high numbers of leptin receptors found in the hypothalamus, brain stem and other regions of the brain. Rising leptin in a fed state inhibits food intake by suppressing a range of peptides involved in eating behaviour.

Ghrelin is predominantly secreted in the stomach and it too modulates cells found in the hypothalamus by increasing excitatory inputs and decreasing inhibitory inputs. Here we are talking about neurotransmitters. These chemical messengers modulate much of our and our pet’s behaviour and they either make something do something or stop something from doing something.

Whilst dopamine can be both inhibitory and excitatory, ghrelin is seen to have a large influence on the release of dopamine via increases in cell excitability. As dopamine is involved in reward and motivation, ghrelin is thought to target the motivational functions geared to gaining food and to select those which are more rewarding (high calorie).

Findings here

In eating disorders, dopamine is one of the neurotransmitters that gets a lot of attention.

In times of reduced food intake (fussy eating), dopamine neurons are activated, in the short-term rewarding the lack of food. It is considered that it is a physiological response in an attempt to increase motivation to forage for food.

Findings here

However, there are also other mechanisms in which the dopaminergic system comes into play for the fussy eater. A central feature of the dopamine neuron response is that it is triggered by unexpectancy.

After receiving an unexpected reward like food (or how many likes our recent post has got on social media) a dopamine surge is elicited.

When this becomes a regular occurrence, the dopamine signal is triggered by the conditioned stimulus in predicting the reward. However, the dopamine system does not respond when the reward is received. If the reward is predicted, then not received, there is a dip in dopamine activity. What this means, is that your dog may do the song and dance ready for their bowl of food, but then walk a way as soon as it is placed in front of them. The reward they predicted (tasty food), isn’t what was received.

The other neurotransmitter that gets a little attention in terms of eating behaviour is serotonin.

5-HT has a well confirmed role in the regulation of eating behaviour. Manipulations to increase it have led to reduced eating behaviour and those to reduce it precipitate binge eating behaviour.

Findings here

This suggests another multifactorial mechanism that indirectly effects eating behaviour.

Serotonin is a key player in feelings of nausea – so higher levels could be produced in response to something not sitting quite right in the digestive system.

Poor serotonin metabolism can also contribute to high levels.

Whenever something is produced in the body,it needs to be used and then broken down. Serotonin is metabolised largely by monoamine oxidase (MAO) so it stands to reason that MAO inhibitors can contribute to high levels in the body. Sadly, certain insecticides found on flea and tick collars contain MAO inhibitors.

Findings here

There are also certain dietary supplements that can increase 5-HT including ginseng, turmeric, rhodiola rosea, l-theanine and St. John’s Wort.

There is also the link between high serotonin levels, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive type behaviours, suggesting that there is also a place for stress behaviour coinciding with fussy eating patterns.

Stress

Stress is a biological response to a perceived threat. It consists of two elements; the fight or flight response and the rest and recover response. During the fight or flight response,resources are directed to where they are needed and away from the digestive system.This we can get on board with. How many times, during stressful experiences,have you just not wanted to eat? Corticotropin-releasing hormone is released as part of the stress response, and it is conclusively linked with decreased eating patterns.

Findings here

This can apply to our dogs too. If they are faced with chronic stressors like health issues or environmental challenges including people and other pets, then their resources will largely be diverted away from their digestive system.

Yet, there is also evidence which links stress to increased eating patterns. This is largely due to the resources utilised in the stress response and the body seeking energy-dense foods. Repeated and uncontrollable stress dysregulates the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis; this in turn activates the dopaminergic system of which we mentioned earlier. This is why hyperpalatable foods are so important, if in fact you are addressing eating behaviour during and when recovering from a stressor.

So where does this all leave us when tackling a fussy eater?

They could of course simply not like the food they are being offered. In terms of reward pathways, it’s just not lighting their fire.There could be some learned behaviour that is telling them to avoid the food on offer; if they have felt rubbish after eating it before, then they’d do well to avoid it in future. This doesn’t even have to be sinister in terms of a gastro bug, it could merely be a sensitivity. It could be due to lack of digestion from a poorly functioning liver or pancreas. Long term medication use could have resulted in limited stomach acid or there could be poor integrity in the gut that warrants some healing. There could be a range of underlying issues like GERD or SIBO, of which just make mealtimes and the following digestion, particularly uncomfortably. This can also apply to dental issues. Whether current or past. Dogs are incredibly good at hiding their pain or discomfort, it wouldn’t have boded well in terms of evolution; a sign of weakness places them as an easy target for predators. So, its up to us to observe and notice patterns in their behaviour.

We must also consider stress. For both human and pet. If they are exposed to acute or chronic stress, it could remove their desire to eat. That said, as an owner managing a fussy eater, the owner too can become stressed and anxious that the dog isn’t getting the nutrients they need to thrive. Unfortunately for us, dogs have incredible olfactory capabilities, meaning they can smell our stress! They also have this capacity to mirror our emotions. And so, when they don’t eat,we get stressed, so they get stressed and may be even less likely to eat.

Top Tips for Managing a Fussy Eater:

- First of all, eliminate any physical reasons why your dog may not be eating (blockages, dental issues etc).

- Establish mealtimes – there’s no unexpected reward if a bowl of food is always laid out.

- Ditch the dry – what is more boring than the same bowl of pellets every mealtime?

- Offer fresh food with a range of tastes, aromas and textures.

- Variety is the spice of life – use novel proteins – what’s more unexpected than novelty? This can also be helpful if you are concerned your dog may have a sensitivity to certain foods.

- Cooking alters the aroma and texture of many foods so this can be a great way to entice.

- Offer food in bowls or plates,or even on wooden boards. There is no categoric link between height of feeding and gastric torsion in dogs, so consider at what level you offer their meals; do they need to be raised.

- Consider the material of the bowl/plate you offer. Some dogs prefer porcelain, some prefer glass. The aroma from plastic bowls, especially if they have been in the dishwasher can be off-putting. Remember a dog’s nose is around 40 times better at smelling things than us humans.

- Where do you feed your dog and at what time? If there is always something more interesting going on, food can fall foul. Offer mealtimes in quiet areas of the home and when it’s calm. If you have a multi-pet home, do they have the space to eat and digest? Or does the presence of other pets become a stressor for them?

- Manage stress for both human and dog!

Thanks for reading!

MPN Team x

Customer Reviews

Explore related products

Related articles

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Best Diet for Struvite Crystals in Dogs

Mar 13 2024

•

5 mins

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Oxalate Stones – What You Need to Know

Jul 13 2023

•

2 mins 40 secs

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Cysteine Stones … Everything You Need to Know

Jun 01 2023

•

3 mins 50 secs

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

The Ultimate Guide to Urinary Stones

Mar 22 2023

•

7 mins 46 secs

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

3 Tips to Support Your Pet’s Urinary Health

May 26 2022

•

4 mins 46 secs

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

What Does the Microbiome Have to Do With My Dog’s Bladder Stones?

May 24 2022

•

6 mins 39 secs

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

What Can I Do For My Dog’s Bladder Stones

Nov 04 2021

•

4 mins 56 secs

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

A Brief Guide to The Canine Urinary System

Oct 06 2021

•

5 mins 6 secs

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Why Does My Dog Need Minerals – Part Two

Sep 23 2021

•

12 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Why Does My Dog Need Minerals – Part One

Sep 22 2021

•

7 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Does My Pet Need to Detox

Apr 15 2021

•

8 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Obesity in Pets Part 1

Feb 25 2021

•

9 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Why Is My Dog A Fussy Eater?

Jan 18 2021

•

10 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

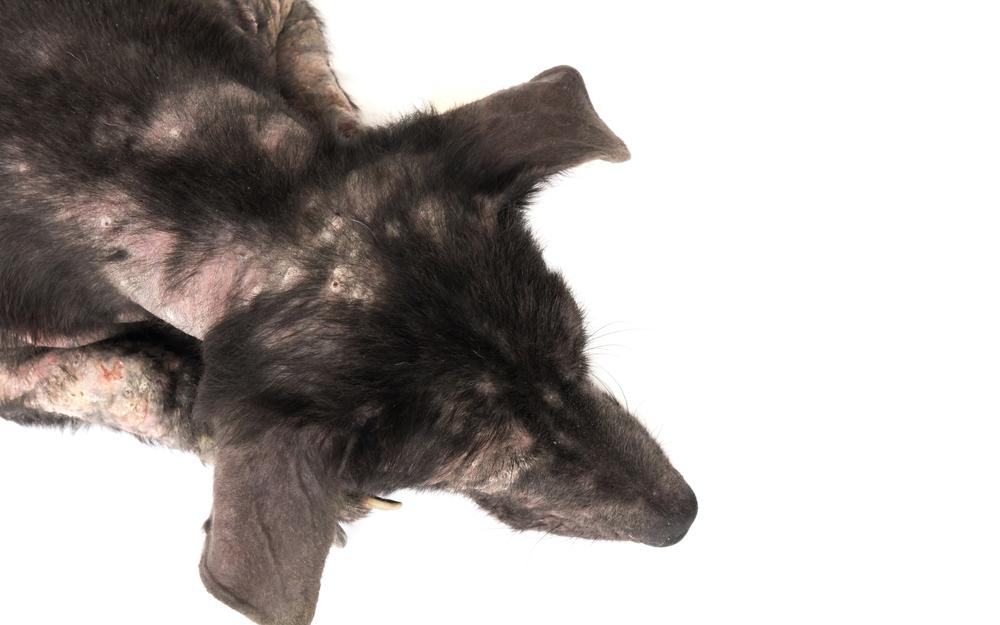

Why is My Dog Losing His Hair?

Jan 04 2021

•

7 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Why is Magnesium So Important to Your Pet

Oct 02 2020

•

10 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

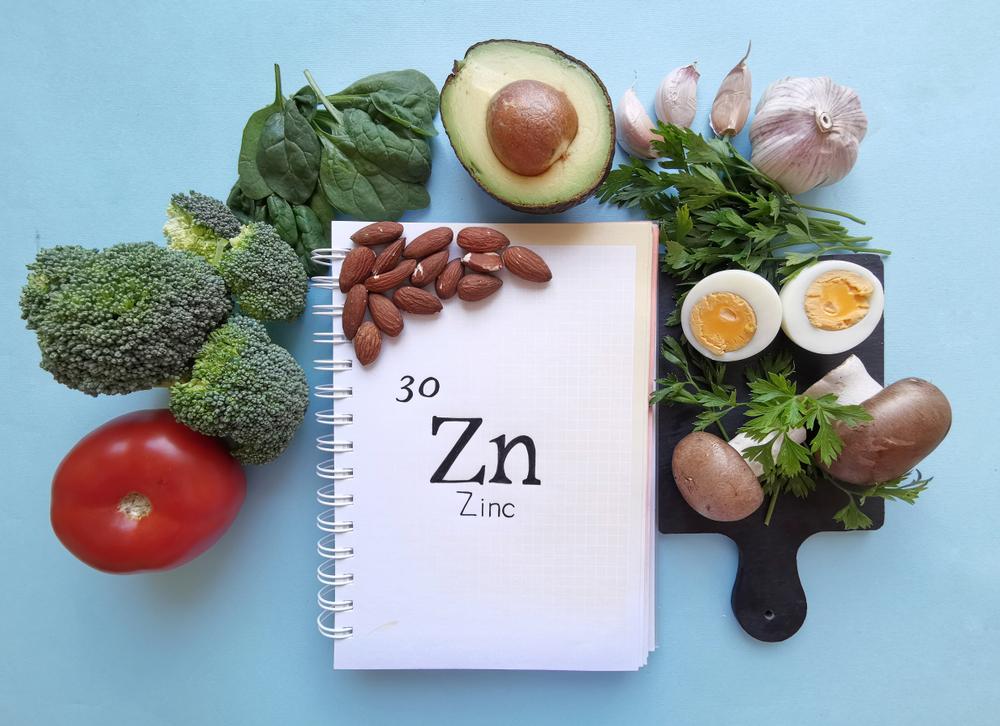

Why Zinc is Important for your Dog

Sep 10 2020

•

8 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

7 Wonderful Herbs for Dogs

Jul 06 2020

•

9 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

Does My Dog Have a Vitamin Deficiency?

May 04 2020

•

15 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

The Ultimate Natural UT Guide for Pets

Apr 14 2020

•

9 min read

AllergiesDietary NeedsGut HealthAnxietyDigestionItching & AllergiesKidney HealthLiver HealthPancreatitisUrinary Issues

7 Top Reasons to use Clay in your Dog’s Diet Regime

Feb 20 2020

•

5 min read

✕